- Home

- Our Community

- Sacraments at St. Elizabeth Seton

-

Parish Life

- Calendar of Events

- News Archive

- Week of Reconciliation

- Catholic Women's Guild

- Our Ministries

- Knights of Columbus

- Society of St. Vincent de Paul

- Our Nativity Sets

- Our Parish Library

- Community Bread

- Saints' Page

- Lent Schedule

- Our Parish Library

- Parish Calendar

- Christmas Nativities

- Echoes of Christmas

- Friday Fish Fry

- Soup and Movie - Lent

- Reconciliation & Lent

- High School Graduation Bursary

- St. Elizabeth Seton

- Mary Prayer Service

- Our Faith

- Bulletin

- Contact Us

- Search

All Saints' Stories

Sr. Thea Bowman, Servant of God

Thea was born on December 29, 1937 in Yazoo City, Mississippi. She was the granddaughter of a slave and the only child of a doctor and a teacher. Her father was practicing in New York, but an aunt convinced him to up and leave for Mississippi to bring quality medical care amidst the facism and prejudices inherent in the South.

The Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration from La Crosse, Wisconsin, opened a school in her Canton, Mississippi, hometown. They built a Church and a school to provide for the spiritual and educational needs of the Black children, whose education suffered from the effects of segregation. It was the Gospel joyfulness of those missionaries that impressed Thea and inspired her to convert to Catholicism at the age of nine. Thea exuded that Gospel joyfulness all her life.

At age fifteen, Thea left her hometown to enter as an Aspirant. Thea experienced open racial prejudice while there and she perservered through hard times. Her outgoing demeanor and tenacious love of Christ and the Church won over many of her detractors.

Thea was intellectually gifted. Sister Thea was assigneed to teach grade school in La Crosse, and then eventually at her home in Canton, Mississippi. She left there in 1965 to head to the Catholic University of America in Washington D.C. She earned her masters and doctorate in English. She then accepted a professorship at her alma mater, Viterbo College.

Through the turbulent times of the Civil Rights era, Thea wanted to bring great awareness of her beloved culture and promote greater harmony and mutual respect among people who looked different from one another. In 1978 she returned home to take care of her aging parents. She served as director for intercultural affairs in the Diocese of Jackson. In her work of overcoming the divisions in the Church and Society, she was one of the founding faculty meembers of the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University in New Orleans.

1n 1984, after burying both of her parents, Sister Thea was stricken with breat cancer. The chemotherapy treatments weakened her pysically to the point where she needed a wheel chair much of the time. She maintained her work touring the world giving speeches and addresses. About a year before her death, she was invited to address the Bishops of the United States. She gave a rousing speech articulating the Black Catholic experience in the United States, and the need for their fuller participation in the life of the Church which was met with a standing ovation.

Sister Thea died on March 30, 1990 and the cause for her canonization was opened in 2018 where she was declared 'Servant of God', the first step toward canonization.

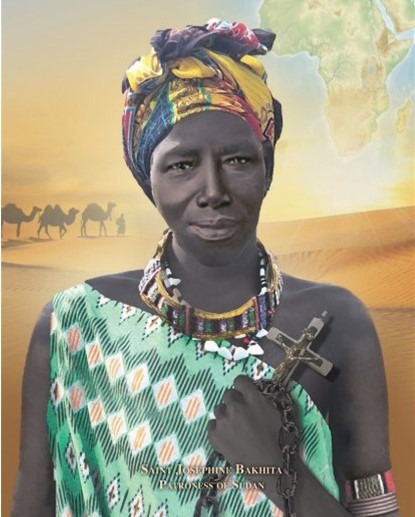

St. Josephine Bakhita

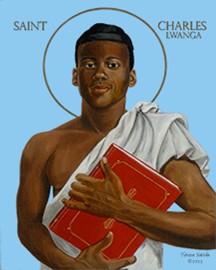

St. Charles Lwanga & Companions

The persecution started in 1885 after Mwanga, a ritual pedophile, ordered a massacre of Anglican missionaries, including Bishop James Hannington who was the leader of the Anglican community. Joseph Mukasa Balikuddembe, the Catholic major-domo of the court and a lay catechist, reproached the king for the killings, against which he had counseled him. Mwanga had Balikuddembe beheaded and arrested all of his followers on 15 November 1885. The king then ordered that Lwanga, who was chief page at that time, take up Balikuddembe's duties. That same day, Lwanga and other pages under his protection sought baptism as Catholics by a missionary priest of the White Fathers; some hundred catechumens were baptized. Lwanga often protected boys in his charge from the king's sexual advances.

On 25 May 1886, Mwanga ordered a general assembly of the court while they were settled at Munyonyo, where he condemned two of the pages to death. The following morning, Lwanga secretly baptized those of his charges who were still only catechumens. Later that day, the king called a court assembly in which he interrogated all present to see if any would renounce Christianity. Led by Lwanga, the royal pages declared their fidelity to their religion, upon which the king condemned them to death, directing that they be marched to the traditional place of execution. Three of the prisoners, Pontian Ngondwe, Athanasius Bazzekuketta, and Gonzaga Gonza, were murdered on the march there.

When preparations were completed and the day had come for the execution on 3 June 1886, Lwanga was separated from the others by the Guardian of the Sacred Flame for private execution, in keeping with custom. As he was being burnt, Lwanga said to the Guardian, "It is as if you are pouring water on me. Please repent and become a Christian like me."

Twelve Catholic boys and men and nine Anglicans were then burnt alive. Another Catholic, Mbaga Tuzinde, was clubbed to death for refusing to renounce Christianity, and his body was thrown into the furnace to be burned along with those of Lwanga and the others. The ire of the king was particularly inflamed against the Christians because they refused to participate in sexual acts with him. Lwanga, in particular, had protected the pages. The executions were also motivated by Mwanga's broader efforts to avoid foreign threats to his power. According to Assa Okoth, Mwanga's overriding preoccupation was for the "integrity of his kingdom", and perceived that men such as Lwanga were working with foreigners in "poisoning the very roots of his kingdom". Not to have taken any action could have led to suggestions that he was a weak sovereign.

She was born around 1869 in Darfur (now in western Sudan) in the village of Olgossa, west of Nyala and close to Mount Agilerei.[1] She was of the Daju people; her respected and reasonably prosperous father was brother of the village chief. She was surrounded by a loving family of three brothers and three sisters; as she says in her autobiography: "I lived a very happy and carefree life, without knowing what suffering was".

Slavery

In 1877, when she was 7–8 years old, she was seized by Arab slave traders, who had abducted her elder sister two years earlier. She was forced to walk barefoot about 960 kilometres (600 mi) to El-Obeid and was sold and bought twice before she arrived there. Over the course of twelve years (1877–1889) she was sold three more times and then she was finally given her freedom

'Bakhita' was not the name she received from her parents at birth. It is said that the trauma of her abduction caused her to forget her original name; she took one given to her by the slavers, bakhīta (بخيتة), Arabic for 'lucky' or 'fortunate'. She was also forcibly converted to Islam.

In El-Obeid, Bakhita was bought by a rich Arab who used her as a maid for his two daughters. They treated her relatively well, until after offending one of her owner's sons, wherein the son lashed and kicked her so severely that she spent more than a month unable to move from her straw bed. Her fourth owner was a Turkish general, and she had to serve his mother-in-law and his wife, who were cruel to their slaves. Bakhita says: "During all the years I stayed in that house, I do not recall a day that passed without some wound or other. When a wound from the whip began to heal, other blows would pour down on me."

She says that the most terrifying of all of her memories there was when she (along with other slaves) was marked by a process resembling both scarification and tattooing, which was a traditional practice throughout Sudan.[10][11] As her mistress was watching her with a whip in her hand, a dish of white flour, a dish of salt and a razor were brought by a woman. She used the flour to draw patterns on her skin and then she cut deeply along the lines before filling the wounds with salt to ensure permanent scarring. A total of 114 intricate patterns were cut into her breasts, belly and into her right arm.

By the end of 1882, El-Obeid came under the threat of an attack of Mahdist revolutionaries.[14] The Turkish general began making preparations to return to his homeland and sold his slaves. In 1883, Bakhita was bought in Khartoum by the Italian Vice Consul Callisto Legnani, who did not beat or punish her.[15] Two years later, when Legnani himself had to return to Italy, Bakhita begged to go with him. At the end of 1884 they escaped from a besieged Khartoum with a friend, Augusto Michieli. They travelled a risky 650-kilometre (400 mi) trip on camelback to Suakin, which was the largest port of Sudan. In March 1885 they left Suakin for Italy and arrived at the port of Genoa in April. They were met there by Augusto Michieli's wife, Maria Turina Michieli, to whom Legnani gave ownership of Bakhita. Her new owners took her to their family villa at Zianigo, near Mirano, Veneto, about 25 km (16 mi) west of Venice.[10] She lived there for three years and became nanny to the Michieli's daughter Alice, known as 'Mimmina', born in February 1886. The Michielis brought Bakhita with them back to the Sudan where they stayed for nine months before returning to Italy.

Conversion to Catholicism and freedom

Suakin on the Red Sea was besieged but remained in Anglo-Egyptian hands. Augusto Michieli acquired a large hotel there and decided to sell his property in Italy and to move his family to Sudan permanently. Selling his house and lands took longer than expected. By the end of 1888, Turina Michieli wanted to see her husband in Sudan even though land transactions were unfinished. Since the villa in Zianigo was already sold, Bakhita and Mimmina needed a temporary place to stay while Micheli went to Sudan without them. On the advice of their business agent Illuminato Cecchini, on 29 November 1888, Michieli left both in the care of the Canossian Sisters in Venice. There, cared for and instructed by the Sisters, Bakhita encountered Christianity for the first time. Grateful to her teachers, she recalled, "Those holy mothers instructed me with heroic patience and introduced me to that God who from childhood I had felt in my heart without knowing who He was."[16]

When Michieli returned to take her daughter and maid back to Suakin, Bakhita firmly refused to leave. For three days, Michieli tried to force the issue, finally appealing to the attorney general of the King of Italy; while the superior of the Institute for baptismal candidates (catechumenate) that Bakhita attended contacted the Patriarch of Venice about her protegée's problem. On 29 November 1889, an Italian court ruled that because the British had outlawed slavery in Sudan before Bakhita's birth and because Italian law had never recognized slavery as legal, Bakhita had never legally been a slave.[17] For the first time in her life, Bakhita found herself in control of her own destiny, and she chose to remain with the Canossians.[18] On 9 January 1890 Bakhita was baptized with the names of 'Josephine Margaret' and 'Fortunata' (the Latin translation of the Arabic Bakhita). On the same day, she was also confirmed and received Holy Communion from Archbishop Giuseppe Sarto, the Cardinal Patriarch of Venice and later Pope Pius X.[19]

Canossian Sister

Church of the Holy Family, Schio

On 7 December 1893, Josephine Bakhita entered the novitiate of the Canossian Sisters and on 8 December 1896, she took her vows, welcomed by Cardinal Sarto. In 1902 she was assigned to the Canossian convent at Schio, in the northern Italian province of Vicenza, where she spent the rest of her life. Her only extended time away was between 1935 and 1939, when she stayed at the Missionary Novitiate in Vimercate (Milan); mostly visiting other Canossian communities in Italy, talking about her experiences and helping to prepare young sisters for work in Africa.[19] A strong missionary drive animated her throughout her entire life - "her mind was always on God, and her heart in Africa".[20]

During her 42 years in Schio, Bakhita was employed as the cook, sacristan, and portress (doorkeeper) and was in frequent contact with the local community. Her gentleness, calming voice, and the ever-present smile became well known and Vicenzans still refer to her as Sor Moretta ("little brown sister") or Madre Moretta ("black mother"). Her special charisma and reputation for sanctity were noticed by her order; the first publication of her story (Storia Meravigliosa by Ida Zanolini) in 1931, made her famous throughout Italy.[2][21] During the Second World War (1939–1945) she shared the fears and hopes of the townspeople, who considered her a saint and felt protected by her presence. Bombs did not spare Schio, but the war passed without a single casualty.

Her last years were marked by pain and sickness. She used a wheelchair but she retained her cheerfulness, and if asked how she was, she would always smile and answer: "As the Master desires." In the extremity of her last hours, her mind was driven back to her youth in slavery and she cried out: "The chains are too tight, loosen them a little, please!" After a while, she came round again. Someone asked her, "How are you? Today is Saturday," probably hoping that this would cheer her because Saturday is the day of the week dedicated to Mary, mother of Jesus. Bakhita replied, "Yes, I am so happy: Our Lady... Our Lady!" These were her last audible words.[22]

Bakhita died at 8:10 PM on 8 February 1947. For three days, her body lay in repose while thousands of people arrived to pay their respects. Her remains were translated to the Church of the Holy Family of the Canossian convent of Schio in 1969.